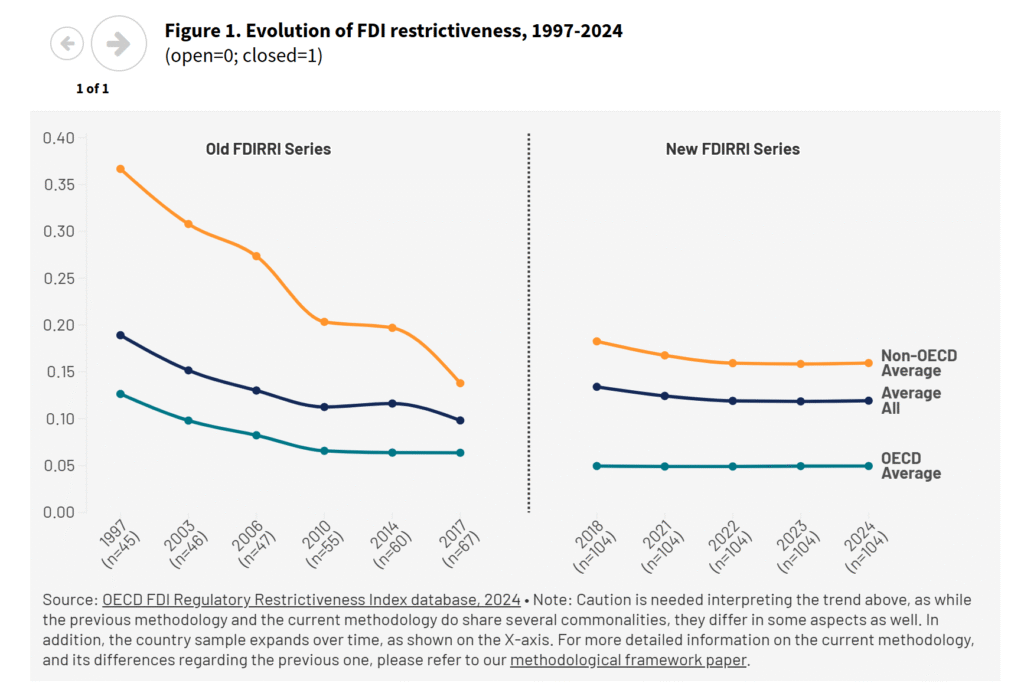

For the first time since 2018, global restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) have edged up, albeit only by a notch. The OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (FDIRRI) shows that average statutory barriers – e.g. foreign equity caps, foreign investment screening, restrictions on key foreign personnel and other restrictions – increased marginally in 2024, following decades of progressive liberalisation across OECD and non-OECD economies (Figure 1).

The findings are presented in the new OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index 2024: Key findings and trends, which provides a global overview of where FDI restrictions are concentrated, how they are evolving, and which reforms could yield the greatest impact. The report is supported by two companion resources: the FDIRRI Scores database and the FDIRRI Regulatory database.

What drove the rise in restrictions in 2024?

Average restrictiveness rose slightly from 0.1186 in 2023 to 0.1193 in 2024 across the 104 economies covered. While modest in size, this change signals that the long-standing trend of gradual liberalisation can no longer be taken for granted.

The rise reflects contrasting policy directions. On one side, several economies, mostly outside the OECD, eased restrictions in selected areas: India opened parts of the space sector to greater foreign participation, while keeping limits on some sensitive activities; Egypt removed majority local-ownership requirements for desert land, which includes land reclaimed for cultivation, thereby expanding opportunities in the agricultural sector; Viet Nam clarified that selected digital services are fully open; and Indonesia repealed nationality-based leadership rules in large-scale electricity projects. At the same time, other economies tightened foreign equity caps or reinforced approval requirements in sectors such as energy, financial services and critical minerals.

The net effect was the first global – albeit small – increase in measured restrictiveness in six years. This shift in the policy trend may signal that tighter statutory restrictions could become more prominent in strategic sectors in the years ahead.

This development coincides with a period in which national security screening policies are evolving rapidly and reshaping the wider FDI policy landscape. While not reflected in the FDIRRI scores, these measures are tracked and reported for transparency. In 2024, among the 104 economies monitored, several OECD members broadened or reinforced their national security screening regimes, and two non-OECD economies adopted new cross-sectoral frameworks.

Why does it matter?

FDI remains a cornerstone of open, resilient economies. It brings capital, technology and managerial know-how; supports integration into global value chains; and can advance broader objectives such as gender equality, skills development, decarbonisation and innovation-led productivity growth (see OECD FDI Qualities Initiative).

Yet global FDI flows have remained subdued over the past decade, reflecting weaker growth prospects, tighter financing conditions and policy uncertainty. In this context, additional barriers risk deterring potential beneficial projects and contributing to a fragmentation of global investment.

Tracking openness through the FDIRRI

The FDIRRI is a transparent, comparable measure of statutory restrictions on FDI. It captures foreign equity limits, screening requirements to the extent they are based on economic criteria, restrictions on key foreign personnel, and other operational barriers (e.g. land ownership rules or profit repatriation limits). Measures used solely for national security are recorded for transparency but do not contribute to FDIRRI scores. By focusing on “rules on the books”, the FDIRRI offers an objective reference point for trends in de jure openness.

What lessons can be drawn from history?

Experience from past decades highlights the risks of protectionist approaches to foreign investment. In the 1970s and 1980s, many countries maintained explicit entry controls and performance requirements on FDI, including equity restrictions and joint-venture requirements. These measures were often justified as ways to protect infant industries, safeguard employment, secure a domestic share of rents, ensure technology transfer, or guard against harmful foreign investors.

While such policies may have been well-intentioned and effective in specific circumstances, historical experience exposed their limitations. Over time, governments recognised that restrictive regimes could deter investment, reduce competition, and discourage projects most likely to support productivity spillovers and integration into global value chains. OECD economies began dismantling barriers in the 1970s and 1980s, followed by many developing countries from the 1980s onwards. Evidence of the benefits of more open, export-oriented strategies reinforced this shift, with many countries moving from restricting to actively promoting FDI.

As the empirical evidence consistently shows that lower statutory restrictions are associated with stronger inward FDI performance, a return to protectionist measures in today’s context of heightened geopolitical divides risks reversing past gains, further deterring investment and increasing market fragmentation, thereby reducing potential productivity spillovers and undermining long-term competitiveness.

Wherever possible, non-discriminatory measures should be preferred when regulating to protect domestic interests, as discriminatory approaches often entail lasting economic costs. Where such measures are deemed necessary, they should remain proportionate, be clearly linked to measurable policy objectives, and be subject to regular review to ensure their continued relevance and value for money.

What key takeaways for policymakers?

Lowering statutory restrictions on FDI has generally proved effective in attracting capital and promoting greater economic efficiency. To maximise the benefits of openness, reforms should be paired with broader policies that strengthen investment’s contribution to sustainable growth, skills, gender equality, innovation and decarbonisation, as highlighted in the OECD’s Policy Framework for Investment and FDI Qualities Initiative. At the same time, contemporary FDI policies are increasingly shaped by security and resilience considerations, requiring policymakers to balance openness and efficiency objectives with more stringent security-related conditions for investors.

Experience and evidence point to several key lessons for policymakers:

- Design investment security policies carefully. Governments have a sovereign right to safeguard national security and other public interests, but policies that discriminate against foreign investors may entail costs in terms of forgone investment and reduced efficiency. Mechanisms to address risks associated with FDI should be transparent, proportionate, accountable, and non-discriminatory, as set out in the OECD Guidelines for Recipient Country Investment Policies relating to National Security. Well-calibrated safeguards enable governments to manage security risks effectively without discouraging beneficial investment.

- Keep liberalisation on the agenda. Foreign equity caps remain the most widespread barrier, especially in transport, media, telecommunications and agriculture. Where conditions allow, their removal can broaden opportunities for more productive investment and improve capital allocation. Ultimately, easing barriers to FDI can also help revitalise global investment.

- Focus on services. Barriers in finance, logistics, communications and professional services are both common and costly. Liberalising services, including broader cross-border trade restrictions identified in the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, can help lower costs, improve competitiveness and boost economy-wide productivity.

- Address regional gaps. OECD countries are generally more open, with restrictions concentrated in a few strategic sectors. In contrast, many non-OECD economies, particularly in the Middle East, Africa and parts of Asia, maintain broader barriers, such as reciprocity requirements or land ownership rules. Targeted reforms in these regions could yield significant investment and efficiency gains.

The way forward

The 2024 FDIRRI results remind us that the path of FDI policy reform is neither linear nor guaranteed. Even a modest increase in restrictiveness is an important signal, reflecting a complex environment where liberalisation and new constraints coexist, shaped by domestic priorities and evolving security and other geopolitical considerations.

The stakes are high. Global competition for investment is intense, and economies that retain open, predictable and non-discriminatory regimes are better placed to attract capital, foster innovation and strengthen long-term growth. Both historical experience and recent evidence point in this direction.

As published on the OECD